The Search: A real-life adoption story

Updated: Jul 12, 2023

A Seek-and-Find Adoption Tale:

Adoptee Shares Joy and Pain of Adoption Journey

This article first appeared as the cover story in the October 2022 edition of Today Magazine, our monthly publication

By Katherine Trinh Napier — Special to Today Magazine

I REMEMBER THE MOMENT I stepped off the plane after spending over 24 hours shoulder to shoulder with two people I’ve never met and will likely never see again. I remember thinking that this was a homecoming — technically.

There are people who identify closely with the country where they were born or where their family came from. Me, on the other hand … I remember trying and failing to find deep inside of me a part that identifies with this place in some way, even though I was born here, after all.

I had a conversation with the stranger on the airplane who sat next to me, a karate instructor. He asked me what I was going to do in Vietnam, and since I’m obviously Asian, he asked if I was visiting family.

Hopefully, I thought to myself.

Instead, I said that I was staying with my boyfriend’s aunt for a vacation and didn’t have any family in Vietnam. That I knew.

I told him that it was actually my first time back in Vietnam in 19 years and I was on a mission to find my birth parents.

ADOPTION QUESTIONS

I was just six months old when I was adopted, renamed Katherine, and flown to the United States, where I was raised by Jack and Diane — yes, like the John Mellencamp song. I grew up in Canton and still live there today.

Growing up, I always knew I was adopted. Even if my parents didn’t tell me, it would be impossible not to know considering the obvious differences in skin tone, eye shape and hair color.

That being said, knowing I was adopted didn’t stop me from having questions all my life.

Why was I given up? Do my birth parents ever think of me? What do they look like? Do I look anything like them? Whose nose did I get? Whose lips?

According to a study of American adolescents conducted by the Search Institute, 72% of adopted adolescents wanted to know why they were adopted and 65% wanted to meet their birth parents. Like me, they probably wanted to know why they were given up and were eager to put a face to the people whose genes gave them their own.

In my sophomore year of high school, I read a book called “Twenty Things Adopted Kids Wish Their Adoptive Parents Knew” by Sherrie Eldridge. The first item on the list was: “I suffered a profound loss before I was adopted.”

There was a dull, constant pain present for all my life caused by the knowledge that, for whatever reason, my birth parents didn’t want me. The hurt was worse at some points in my life, but by the time I reached my late teens it became more of a curiosity than anything else.

A WOMAN NAMED LOI THI MAI HIEN

All I knew at that point was my birth mother’s name, Loi Thi Mai Hien — listed as last name, middle name, first name — and my birth name, Loi Thi Mai Trinh, and that I was left at the hospital soon after being born.

“Abandoned,” the birth certificate said.

With the encouragement of my adoptive mother, who is simply Mom to me, I had taken an Ancestry.com test with no promising results except for an exhaustive list of fourth cousins. Growing up, I never had much hope of finding my birth parents, who were all the way on the other side of the world. Especially not my birth father. His name was not even listed on the birth certificate.

One summer, my boyfriend Chris — who is Vietnamese and is not adopted — invited me to go to Vietnam with him and stay with his aunt, Di Dinh (pronounced Yi Yinh).

It was the perfect opportunity to fulfill my lifelong longing and find my birth mother. All the way across the world, I brought with me my only lead: my birth certificate. I was born July 9, 2000 and was adopted in January 2001. That year, the U.S. Department of State estimates there were 19,646 adoptions, 736 from Vietnam.

When my parents went to Vietnam they met a couple, Doug and Sarah, who were also from Connecticut and were adopting a baby girl. We were born six days apart, were from the same orphanage, and were both named Katie. We grew up as family friends: often getting together to play dress-up, going to the beach, and eating at our favorite authentic Vietnamese restaurant, The Bamboo Grill in Canton.

NAMESAKE FRIENDSHIP

Mirroring my own childhood in Canton, Katie lived in a small town two hours away from me where there was very little diversity. She felt like no one could relate to the feeling of being adopted and the need/desire to find her birth parents. While she had two other friends who were also adopted, they weren’t as curious as she was.

While she never held any grievances against her birth parents for giving her up for adoption, she did admit to feeling hurt. Like me and many other adopted children, she had separation issues and even night terrors. She described the feeling as being similar to an invisible scar — a reminder of a painful moment in her life that no one else could see, but she will always bear.

It wasn’t until her senior year of high school that Katie started thinking seriously about locating her birth parents, more specifically her mother because her father isn’t listed on the birth certificate either.

I never had much hope of finding my birth mother — after 19 years of not knowing, what’s 19 more?

She is eager to have a connection with the person who birthed her and to finally have all her questions answered. But at the same time, she is scared of being hurt by what her birth mother might say. Her searching process stopped almost as soon as it started because Katie couldn’t find anyone to translate the documents relating to her adoption. After all, they were in Vietnamese.

I was fortunate to have Chris and Di Dinh help me translate my documents, and they knew how to navigate the country. After a couple of days riding around Vietnam on mopeds, going on boat trips and eating amazing food, Chris and I were eating breakfast one morning when Di Dinh told me, translated by Chris, that she found the orphanage I was adopted from and we could go visit.

On our way there, Chris asked me if I was excited or nervous. In all honesty, I never had much hope of finding my birth mother. After 19 years of not knowing, what’s 19 more? But when Di Dinh told me the orphanage might know something, I couldn’t help but get a little hopeful. Off the side of a busy street in Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon) was a paved walkway that led to a white building: the Tam Binh Orphanage Center.

“Tam Binh” translates to “peace of mind” in English. Inside the orphanage, we sat at a big wooden table and were served a fragrant tea. While sipping on the tea, the sound of singing kids could be heard behind closed doors from the adjacent room.

Two women who worked at the orphanage came to talk to us. They were very nice and welcoming but didn’t have much information about my birth mother. They did mention the hospital where I was born might be more helpful. Regretful for not being of much help, they offered us a tour of the orphanage.

My parents had told me that when they came to the orphanage 19 years ago, it was so packed with kids the caregivers would cradle one baby in their arms and the other on their feet.

TOO MANY ORPHANS

On our tour, there were not only babies but also many older kids in classrooms ranging from 4 to 8 years old, and some bigger kids too, as old as 13. Many of them were physically disabled. Chris admitted to me afterward that it was sad seeing so many kids crammed into the very few and little rooms.

Orphans. Like I was. The only difference was that I was fortunate enough to be adopted when I was still a baby.

My parents would always tell me while growing up that strangers on the streets of Vietnam and in the airport on the way back home told my parents how lucky I was to be going to America. And I really was, and still am, very fortunate.

Before we left the orphanage, we said our goodbyes and one of the women gave me a hug. Albeit a little awkward, perhaps I gave her hope. I was once like those babies she cared for and I grew up to be happy and healthy and maybe these kids would too.

On our walk back to the bustling streets of the city, Di Dinh asked me if I wanted to go to the hospital where I was born to try our luck there. Even though I didn’t have much confidence in finding anything, I figured it wasn’t every day I got to go to Vietnam and have people like Chris and Di Dinh willing to help me. So we hopped into another taxi and made our way to Tu Du Maternity Hospital.

Cramped in the backseat of a small car, Chris asked me how I was feeling. Even though I had come on this trip hardly having any hopes or expectations of being successful in my search, I couldn’t help the sinking feeling in my heart when the orphanage staff said they didn’t know anything.

I still had hope that the hospital might have some information. Chris, on the other hand, was more worried about me being disappointed. What if we had come all this way from the other side of the world only to learn nothing?

As we walked the halls of the hospital, I wondered if my birth mother had taken those same steps. What I remember most about the hospital was the waiting. We sat on benches outside an office for the better part of an hour waiting for someone who could talk to us. Finally, a woman in a long white coat came — a doctor.

For a second, I wondered if this could be the doctor who delivered me but quickly realized she was far too young to have delivered me almost 19 years ago to the day. While Di Dinh went to talk to the doctor in her office, she told Chris and me to stay outside. More waiting. I anxiously passed the time playing sudoku on my phone.

OPEN-AND-SHUT CASE

When the door finally opened after what seemed like an eternity, Di Dinh strolled out with the doctor right behind her.

I bowed and greeted her as Chris had taught me. Di Dinh then told me that my mother was 19 years old when she came here to give birth. Exactly the age I was going to be the next day.

Unfortunately, the doctor told her that the hospital destroys records every 10 years, so any record of my birth mother was gone, but some other places could possibly have some information. I was starting to feel like we were just going on a wild goose chase. Then Di Dinh said something to me that Chris couldn’t figure out how to translate.

The next day was my birthday. I couldn’t stop thinking about how at the age of 19, my mother and I were in two very different places. She gave birth to me while my birth father’s whereabouts were unknown. I was enjoying a vacation with my boyfriend. After spending my birthday eating delicious food and lounging around, Di Dinh called Chris and me downstairs. She had a video to show me. It was what Chris didn’t know how to translate back at the hospital.

The video was of the Hmong people, an Asian ethnic group in China and Southeast Asia who typically live in the mountains and other high altitudes. They wear colorful traditional clothing with intricate designs and have dark hair and tan brown skin matching mine.

It was hard to imagine my birth mother being one of them while I grew up in suburban Connecticut wearing band T-shirts and ripped jeans. What occurred at the end of the video was what shocked me the most. One tradition of the Hmong people was/is bride kidnapping, also known as “zij poj niam.” Some translations I found include: “kidnap woman” and “marriage by capture.”

The tradition is one where a man will abduct a woman he wishes to marry. She will remain in captivity until her family finds her or, after three days, she marries the same man who kidnapped her. It was disturbing to see such young girls being forcibly taken from their homes and put through such a situation. Sadly, this custom is also practiced in other parts of the world, according to Google research.

In two days, I had learned that my birth mother was my age when she gave birth to me and that she was possibly a victim of bride kidnapping. Chris again asked me how I felt about all we had learned.

To be honest, I didn’t know. It was weird to feel sympathy for someone I had never seen but who was still my mother. Because she was able to make it to Ho Chi Minh City to give birth to me, I hoped that she had escaped such a life and found a job in the city — and I hoped she is doing okay today.

Still sitting on the couch after watching the video, Di Dinh asked me if I wanted her to continue searching, even after I left in a few days to go back home. There were still other places that might have more information.

I said “yes” — but to be honest, I was content with what I had learned. Even if it wasn’t very much, it was way more information than I had ever expected to gain. I was okay if that was the end of my journey.

If this was the closest I would ever come to know the woman named Loi Thi Mai Hien, then I was okay with that. +

• An award-winning writer, Katherine Trinh Napier is a graduate of Canton High School and the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts (in 2022) — she was the co-editor of her college newspaper

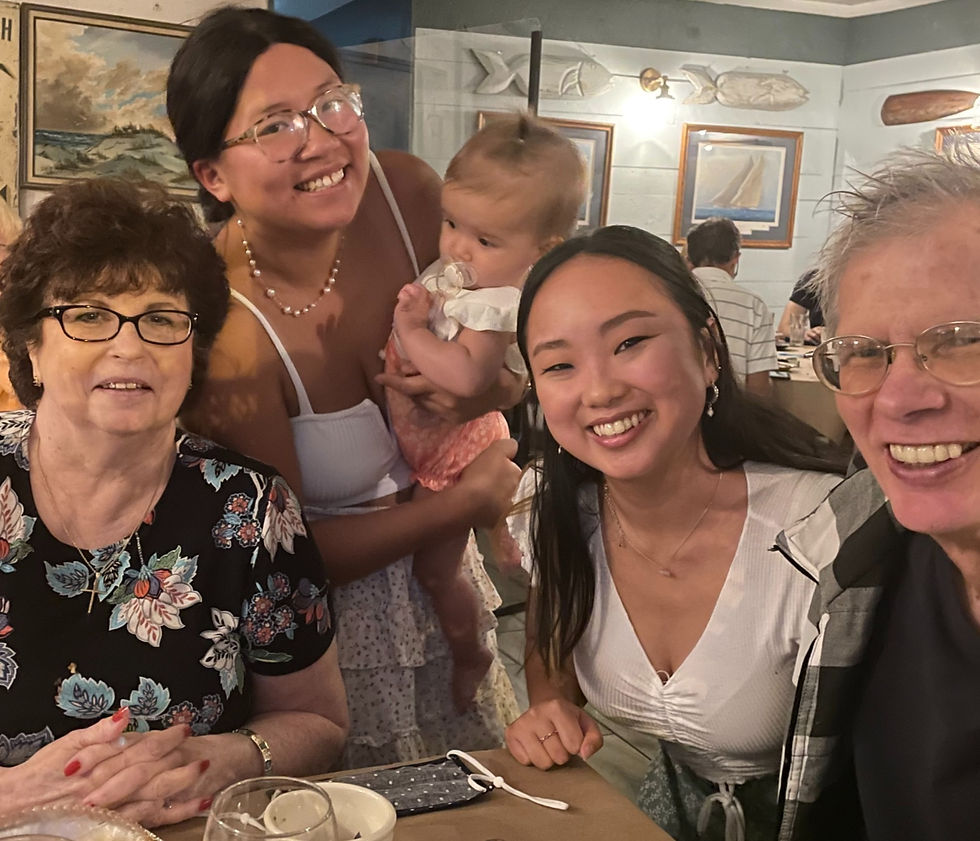

• Katherine has an older sister (Jessica) who was also adopted from Vietnam four years earlier — they have a half-brother (Jeb) from her father’s previous marriage and another half-brother (Johnny) from her mother’s previous marriage

• The Tam Binh Orphanage Center, from whence Katherine was adopted, is also where Oscar-winning actress Angelina Jolie adopted her son Pax in 2007

• Katherine received three first-place SPJ awards in 2022 for articles she contributed to Today Magazine • SPJ = Society of Professional Journalists

• Related Story — Today Magazine wins 12 more SPJ awards

Comments